Wednesday 17 January

The POLE. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected.[i]

These words register the desolation Robert Falcon Scott felt on finding he and his party had been beaten in their race to the South Pole by the Norwegians, lead by Raold Amundsen. Regardless, they ‘built a cairn, put up our poorly slighted Union Jack, and photographed ourselves’. (18 January 1912).

[i] Diary extracts in italics are taken from Captain Scott's Diary, British Library Add. MS 51035, f.39.

The POLE. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected.[i]

These words register the desolation Robert Falcon Scott felt on finding he and his party had been beaten in their race to the South Pole by the Norwegians, lead by Raold Amundsen. Regardless, they ‘built a cairn, put up our poorly slighted Union Jack, and photographed ourselves’. (18 January 1912).

[i] Diary extracts in italics are taken from Captain Scott's Diary, British Library Add. MS 51035, f.39.

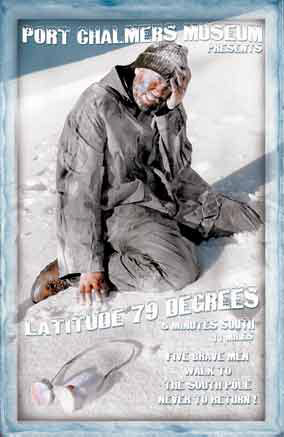

Peter Fitzpatrick’s Latitude 79 degrees 50 Minutes South 11 miles includes a photograph, Pole, which re-enacts this historical moment. Fitzpatrick and four friends, dressed up in cellophane glasses and fake ice-encrusted hair, are transformed into those figures from an heroic age of exploration.

This installation consequently responds both to the drama of Scott’s expedition as well as the history of imag(in)ing Antarctica. Antarctica has long been the subject of speculative images, but photography occupies a particular place in the picturing of Antarctica as providing evidence, a kind of proof of place and record of events.

Although it is nearly one hundred years since Scott and Amundsen reached the South Pole in 1911-12, Antarctica remains a place that many experience only through the power of the imagination or through re-presentations. Latitude 79 provides a thorough re-visioning of Scott’s last great heroic venture onto the wide white page, and all it stands for in the popular consciousness.

“I am just going outside and may be some time”

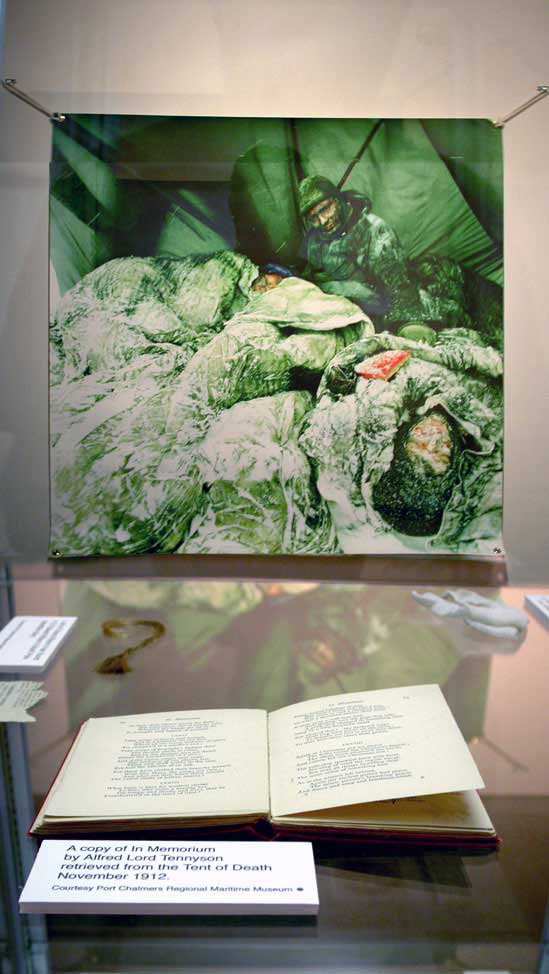

These infamous parting words, spoken by “Titus” Oates, recall the ultimate tragedy of Scott’s expedition: that none of his party survived the return trip from the Pole. Evans died following a head injury, Oates walked out in a blizzard to his death, while the remaining three succumbed to the conditions just 11 miles from the next supply depot. This final scene is mocked up by Fitzpatrick in Tent, a reconstruction of the ‘death tent’, found by a relief party seven months later. This work deals with the ambivalence embodied in the Antarctic explorations, the heroic and unheroic dimensions of such endeavours. For, while Scott’s expedition was ultimately a failure, it was successfully re-coded as an epic adventure, and Scott assigned the status of hero.

Saturday, December 9

At 8pm the ponies were quite done…we camped, and the ponies have been shot

The inherent trickery of the photographic medium is paramount to a reading of Fitzpatrick’s work, as he plays on the relationship between truth and fiction. By holding these opposites in suspense, the processes underlying the act of representation and the systems of belief they encode are exposed. While a certain authenticity of experience is emphasized in Fitzpatrick’s work (Tent, Pole and the photographs of Scott’s men were made in near blizzard conditions on the Pisa Ranges in New Zealand), Latitude 79 relies on the documentary value that we assign photography and the extent to which we, as audience, will go to suspend our disbelief. These are not retouched, enlarged, and coloured photographs, but reconstructions. They question our investment in the ‘truth’, in ‘history’, especially when heroic figures or stories are invoked.

To further this conundrum, Fitzpatrick utilizes strategies of museological display. A Cabinet of Artefacts, a glass-topped vitrine filled with both real and fake ‘artefacts’ from Scott’s voyage, forms a central part of the installation.

Along with Kathleen Scott’s feminine, lacy glove, apparently found on Scott’s body, the display case contains ‘One of the bullet casings used to destroy ponies on route to the South Pole, retrieved from Henry Bowers body’.

The photographic print and the historical object derive their power from their perceived status as indexical items, touched by, or witness to figures and/or events from the past. They also provide an ‘illustrative’ counterpart to Scott’s powerful text in his diary, which was found in the death tent. Consequently, this exhibitionary device provides an ‘object-lesson’, lending further credibility to Fitzpatrick’s project. But because of the unknown degree of deception involved it simultaneously undermines the truth-making exercises expected of institutional display strategies.

Send this diary to my (wife) widow

Fitzpatrick’s intention is not, however, simply to mock Scott in light of revisionist histories. Instead, there is a degree of empathy in his approach that respects the fallibility of humankind, the unpredictability of certain situations. So while his work deconstructs the histories of heroism, it does so with a degree of poignancy. This is evident in the five portraits collectively titled Black flag, in which he re-presents the wives and fiancées of the explorers. Scott’s dependence on his wife, who arrived in New Zealand to greet the great man who was never to return from the icy limits of Antarctica, provides the romantic culmination to his epic narrative.

Ironically, it is the female figures that Fitzpatrick renders as ghostly forms in the manner of historic daguerreotypes in contrast to the overblown colour-saturated portraits of Scott’s men, suggesting that in the end, experiencing the ‘real’ Antarctica gradually dissolved memories of ‘home’. That, in a reversal of our relationship to Antarctica, in the end, being ‘there’ resulted in only being able to imagine being ‘here’. Such ambiguities lie at the heart of Fitzpatrick’s work, which relishes negotiating the treacherous and often slippery slope between the imagined and the real, between the ridiculous and the sublime.[i]

[i] Derek Mahon’s poem repeats Oates’ final words as follows: ‘I am just going outside and may be some time/ At the heart of the ridiculous, the sublime’. See ‘Antarctica’, in Bill Manhire (ed), Wide White Page: Writers Imagine Antarctica, Wellington: VUP, 2004, p. 144.

Cabinet Detail - Tasmanian School of Art

Exhibition Invitation

Install View - Tasmanian School of Art

Install View - Port Chalmers Maritime Museum

Install View - Tasmanian School of Art

Install at Adams Gallery Wellington New Zealand